|

|

|

|

| Low-Level Photography Reports |

| United Kingdom Military Low-Flying Training 'An Essential but Perishable Skill' UK Low Fly System (UKLFS) |

|

| Tornado GR.4A (ZA401 '012') is fitted with a Litening III (AN/AAQ-28) targeting pod. Training sorties are planned to provide the pilot with the maximum benefit and can often combine low-level flying with a medium level element utilising the targeting pod. |

Training gets faster and lower For a student pilot low-level flying skills are taught right from beginning of their flying career working down in height and up in speeds as they progress through the training courses. The Elementary Flying Training (EFT) course consists of 35 hours on the Grob Tutor T.1 it includes some low-level flying where students fly no lower than 500 feet (152m) at 104 knots (193 km/h) or two miles a minute. Students pass to the Basic Fast Jet Training (BFJT) course at RAF Linton-on-Ouse on the Shorts Tucano T.1, this course consists of 125 hours, of which 10% is at low-level. Flying at 208 knots (385 km/h) or four miles per minute students are initially cleared down to a Minimum Separation Distance (MSD) of 500 feet (152m) before being cleared down to 250 feet (76m). They will use a stopwatch and map to navigate while visually estimating their altitude when flying at low-level. On the Advanced Flying Training (AFT) with 208(Reserve) Squadron students fly the BAE Systems Hawk T.1 and experience jet aircraft for the first time and fly at speeds of 420 knots (778 km/h) or eight miles per minute. 30% of the 62 hour course is flown at low-level. Progressing to 19(Reserve) Squadron also at RAF Valley for tactics and weapons training, nearly 40% of the 47 hour course is flown at low-level. Those students that make the Tornado transfer to the XV(R) Squadron at RAF Lossiemouth to the Operation Conversion Unit where the student pilot initially flies six low-level flights with a pilot before they are deemed safe. Once with an operational squadron low-level flying training is continuous to ensure pilots are competent and safe. |

Currently aircraft from a Tornado GR.4 Squadron, as part of the 903 Expeditionary Air Wing, are deployed to Afghanistan under Operation

While much of the preceding time is spent training in the UK, for part of the ‘work up’ he was about to fly out to the United States where Marham Wing will be taking part in a series of three exercises, ‘Red Flag’ and ‘Green Flag’ in Nevada and finally ‘Alberta Focus’ in Canada. Nevada is an ideal training ground for Afghanistan, it is similarly ‘hot and high’ and the landscape is more or less the same. Flying fast and low is an essential part of the Tornado’s capabilities and so training in a similar environment enables aircrew to be ready for the rigors of Afghanistan. Wing Commander Andy Challen, Officer Commanding Marham Ops Wg, a Tornado pilot with over 2,000 hours flying experience recognises that while there are no aerial threats to aircrew in Afghanistan, the dangers are still there; “Everyone has an AK-47 and there are other ground based threats. You can’t relax there is always a surprise waiting to happen. The biggest risk to us is deconfliction with other users of the airspace. We need to make sure, as we do in the crowded airspace in the south of the UK that we don’t get in each others way”. The Tornado offers a graduated response starting with a ‘Show of Presence’ so everyone can see them or a ‘Show of Force’ (SOF) where it is flown fast (600 knots or 1,111 km/h) and low, perhaps as low as 100 feet (30.5m) over a hostile situation to deter any further hostilities. Wg Cdr Challen explained; “If there are issues with a crowd or hostile activities we quite often don’t want to employ a weapon as that could have a worse effect on the ground. Quite often by flying over a crowd extremely fast and extremely low the kinetic sound is enough to disperse them. This is generally lower and faster than we fly in the UK. If we did not train in the UK then we would not be able to do it as safely”.

Sqn Ldr Sharrocks agrees; “As a Tornado GR.4 pilot I can fly the aircraft very accurately over a building or vehicle at very high speed at very low-level. The shock effect can often clear away any insurgents and calm everything down without the need for any ordnance on the ground”. Fly low, fly safe A pilot’s mantra is perhaps; ‘stay low, stay safe’ but to do so requires continuous training, it is accepted that low-level flying skills are perishable. Sqn Ldr Beardmore stated; “If you don’t practise at low-level then it could become a very dangerous environment. The need is there to keep our guys current and make sure that they are safe in how they operate”. If for any reason a pilot has not flown at low-level for a period of time due to a ground based course or illness, then he has to gradually work down to the extreme low-level required. Another pilot will fly a check-ride to make sure his skill sets are up to standard before he goes out with a navigator. Pilots have various check-rides that they do in a year including an annual check-ride. “It is important to monitor their handling skills in the low-level environment”, reported Sqn Ldr Beardmore. Many hours are flown each year at low-level in the UK, to do this safely then it has to be tightly controlled and managed. |

Low-Flying Operations Squadron (LF Ops Sqn)

The LFBC consists of a circle of computer operators known as the ‘Carousel’ who take the pilot’s low-flying bookings and issue them a booking number for each sortie. They use the latest software package Mil-EAMS (Military Extended Aeronautical Messaging Service) supplied by NATS, who provides air traffic control services to aircraft flying in UK airspace. A separate duplicate computer and phone system ensures backup in case of failure. Under the continuous supervision of a Sergeant, LFBC staff will pass to pilots the necessary information regarding availability of the requested LFA, usually requested no more than four hours before take-off. The booking records the pilot’s initials, squadron, aircraft callsign, aircraft type, number of aircraft, departing airfield, LFA entry and exit times and the minimum height to be flown. LFBC staff will check that all requests do not contain anomalies and mistakes over timings and areas transited for the aircraft’s entire routing at low-level. Pilots may request to fly at low-level through a series of LFA’s, helicopters may hover or land to refuel before continuing, all adding to the complexity of the task of checking. After the sortie has been flown the pilot’s squadron will return a form containing the details of the flight, which must be done by the following day. Any deviations to the flight, along with the actual times, are used to update the original booking. All data is held providing a comprehensive database of low-level flying movements. The database is analysed and used to identify a particular aircraft and pilot should there be a complaint that requires investigating. The aircraft’s systems will record flight details, heights, speed, location etc. which again is held pending any investigation.

How low is low? Low-flying for fixed wing aircraft in the UK is defined as below 2,000 feet (610m) Above Ground Level (AGL), while helicopters are considered to be low-flying at 500 feet (152m) AGL. Generally the low flying rules for experienced pilots dictates that they must keep a Minimum Separation Distance (MSD) of at least 250 feet (76m) from the ground or any structure and less experienced pilots must fly with 500 feet (152m) MSD. The British military fixed wing aircraft are cleared normally to fly down to 250 feet (76m) AGL. Helicopters are cleared to fly down to 100 feet (30m) in normal operations. Speed limits apply of 450 knots (833 km/h) with a maximum limit, for attacking targets for example, of 550 knots (1,018 km/h). The UKLFS is also subject to rules regarding the weather and its effect on visibility. For any aircraft flying faster than 140 knots (260 km/h) the pilot must have at least 2.7nm (5km) of visibility, 5,000 feet (1,524m) horizontal and 500 feet (152m) of vertical separation from cloud. Pilots are also instructed whenever possible to cross over coastlines above 500 feet (152m) to avoid large bird populations. Pilots can report high concentrations of birds to the LFBC. Pilots are also instructed not to fly over the same location whenever possible more than two times during the same sortie. Places to avoid

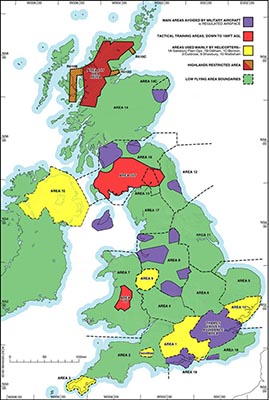

Avoidance areas have been established to prohibit low-level flying over areas of high population densityand in certain types of regulated airspace, such as around most major civilian airfields e.g. Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted airports and the Thames Valley. For avoidance areas helicopters and light aircraft should not over-fly urban areas below 1,000ft (300m) and for rural areas not below 500ft (150m). For other larger fixed-wing aircraft they must not over-fly any avoidance area below 2,000ft (600m). In the case of military low-flying within the UKLFS there are additional NOTAMS known as Yankee’s and Zulu’s. A ‘Y’ series NOTAM refers explicitly to heights between surface and 2,000 feet (610m). A ‘Z’ series NOTAM is a low-flying Temporary Avoidance where the pilot flying at low-level must avoid a location whenever possible. Yankee’s are used for low-flying activities such as; Royal Helicopter Fights, Red Arrows in transit, sports aviation such as gliding and micro-lights centres or for hot air ballooning sites. Zulu’s are used when local events such as; concerts, festivals, filming, racecourse meetings or agricultural shows are notified to the LFBC. Some Zulu’s are seasonal and can be in effect for say six months every year for various reasons. When a pilot books a low-flying sortie he will be asked what are the latest ‘Zulus’ and ‘Yankees’ he is aware of, to make sure he is up to date. NOTAMS can be issued at any time sometimes without notice. A pilot may identify a danger during a sortie such as; balloons or hang gliders to their Squadron who will then refer the sighting to the LFBC who will issue a NOTAM if it is deemed necessary. The LFBC are responsible for the monthly allocation of slots to the Squadrons for the Strike command Air Weapon Ranges at; Tain, Pembrey, Donna Nook and Holbeach. The LFBC will set up Temporary Danger Areas around civilian and military aircraft crash sites, these are usually set at to a height of 5,000 feet (1,524m) AGL with a radius of 5NM (9 km) around the incident. The military are required to spread low-flying operations around the LFA's to minimise the impact of low-flying on the general public. Staff will make sure that each LFA is not overloaded with too many aircraft LFA12 in North Eastern England has a low-flying cap of 15 aircraft at any one time. The routing once at low-level is flexible aircrews are free to deviate from a planned route to avoid poor local weather conditions for example. Whilst some valleys are designated as 'one way' and are deemed to be 'flowed', there are generally no restrictions on where they can fly within the LFA providing NOTAM’s are adhered to and Defined Danger Areas, built up areas and ATZ’s and MATZ’s are avoided. Low-flying Training Areas

Within the UKLFS are three special low-level flying areas called Tactical Training Areas (TTA or ‘Tango Area’) where fixed wing low flying can be authorised down to just 100 feet (30m) AGL for fixed wing aircraft, excluding Hercules which have a 150 feet (45m) limit for Operational low-flying (OLF) training. Helicopters are not allowed within a TTA when it is active. When a TTA is active aircraft that are not booked in to the TTA can only fly down to 500 feet (152m), however during the times the TTA is not active then normal low-flying rules apply. The TTA's are designated with an individual area code, for example LFA 7T, which is within LFA 7 situated in mid Wales. Area 14T (Highlands Restricted Area) is located in the Highlands of Scotland and is used for training with Terrain Following Radar equipped aircraft such as the Tornado GR.4 and C-130 Hercules. TTA’s are only occasionally operational usually available to pilots for just one hour a day known as ‘Tango times’, they account for between 1% and 2% of all low-level flying in the UKLFS. Not every pilot is qualified for OLF if a pilot is required to utilise a particular TTA their Squadron must put in a ‘bid’ to the LFBC perhaps two months in advance for a slot in a TTA or for night-flying. A bid reflects the importance of the training requirement of the sortie. The TTA bid (priority) codes; 1 - Operational urgent usage 2 - Large scale MOD approved exercise 3 - Small scale MOD approved exercise 4 - Work-up prior to deployment 5 - Flight Trials 6 - Unit training to qualification (Qualified Weapons Instructors (QWI), night-vision goggles (NVG) etc.) 7 - Other exercise 8 - Routine training The bids are collated and allocations are made as fairly as possible to each Squadron by the LFBC. Air Defence training can take place over the LFA's, in areas designated as Operational Training Areas (OTA). There are seven OTA's (A to G), OTA Golf for example covers a good part of central Wales. The LFBC are not responsible for handling OTA bookings as they are not part of the UKLFS. A number of military ranges are situated around the UK and are used for low-level conventional and electronic warfare training. Spadeadam in Northumberland is the most sophisticated range containing a large number of realistic threat emulators. It is used regularly by fixed and rotary wing aircraft. |

|

| McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle (98-0131) of 492 FS, 48 FW in October 2009 (DSLR x1.6 sensor + Canon EF 300mm f2.8L f.2.8 -1/3 exposure compensation, 1/640 and ISO 200) |

| United States Air Force F-15E Strike Eagles from the 48th Fighter Wing at RAF Lakenheath in Suffolk frequently make use of the UKLFS. Based in the UK they are subject to the same control as British military aircraft. |

A foreign invasion Use of the UKLFS is reserved exclusively for UK-based aircraft. The United States Air Force aircraft permanently based in the UK are not regarded as foreign visitors, but are subject to the same regulations as UK military aircraft. The 3rd Air Force will place their bookings at short notice with the LFBC in the same way the UK military forces do. Pilots of the 48th Fighter Wing flying the McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle are permitted to fly down to 500 feet (152m) MSD. The Lockheed C-130 Hercules of the 352 Special Operations Group who frequently fly at night are permitted to fly down to 500 feet (152m) MSD in the LFA’s but can fly as low as 150 feet (46m) MSD in the TTA’s. NATO squadrons on approved HQ Air North and Air South exchange visits may be given approval to use the system. During exercises such as the Tactical Leadership Programs (TLP) and Qualified Weapons Instructor Courses (QWIC) NATO member countries are able to use the UKLFS after giving ten days notice. The Royal Danish Air Force (RDAF) and French Air Force (FAF) have reciprocal agreements, which allow them to operate in the UKLFS. These are known as ‘Exercise Blue Sky’ (RDAF) and ‘Exercise Garlic Lemon’ (FAF) approval for such flights should be sought at least three days before the flight. Use by any other NATO aircraft must be approved by MOD giving them at least 30 days prior notice. Foreign aircraft are not allowed to fly lower than is allowed in their own country.

Low-flying at night The UK Night Low-Flying System (UKNLFS) operates differently to that of day time, to provide increased levels of safety. All military aircraft flying below 2,000 feet (610m) have to book their flight details. The UKNLFS is divided into two regions, the Allocated Region (AR) and the Rotary Wing Region (RWR). The RWR includes the Thames Valley Avoidance Area and comprises an area roughly south of a line between the south west coast of Wales across to Ipswich. The AR covers the rest of the UK north of this line. The UKNLFS is deemed to be in operation 30 minutes after sunset and ends 30 minutes before sunrise. Night flying by fast jets should end at 23:00 local time unless special permission is granted by the MOD. The RWR is put aside for helicopter pilots to operate safely at night time, should a fixed wing aircraft wish to operate with the RWR then the flight must be booked ten days in advance and a corresponding NOTAM will be created. RAF Lyneham which is within the RWR has a corridor set up to allow its based C-130 Hercules to embark on low-level flights into the AR. Helicopters can use the AR after seeking permission from LF Ops unless they are a Search and Rescue (SAR) for example. There are also dedicated Helicopter Night Training Areas which can be found around the UK for SAR, NVG training and other similar activities. Both the AR and RWR are divided in to Night Areas which are in turn divided in to Night Sectors and deconfliction between aircraft sorties is aided by the allocation of these sectors to particular squadrons, the pilots are then responsible for their own deconfliction. |

|

| 11(AC) Squadron Tornado GR.4s (ZG726 '125' and ZA614 '076'). (DSLR x1.6 sensor + Canon EF 24-105mm (70mm) f4L at 2.5 seconds f8 -2/3 ISO 100 with a tripod but without flash). |

| A II(AC) Squadron Tornado GR4 being prepared in a hardened aircraft shelter (HAS) at RAF Marham for a lowlevel night flying sortie as part of its work-up for operations in Afghanistan. Pilots frequently train at night with sorties often commencing as the sun sets. The UK Night Low-Flying System (UKNLFS) is deemed to be in operation 30 minutes after sunset and ends 30 minutes before sunrise. Night flying by fast jets should end at 23:00 local time unless special permission is granted by the MoD. |

Preparing for a low-level sortie A front-line aircraft pilot described a mission as a 24 hour operation. The day before, following a weather brief at 17:00 and using a list of serviceable aircraft, the pilot's Wing Commander or Squadron Leader will plan missions based on what crews need to stay current on a particular activity and to provide them with as much variety as possible. For flight planning military aircrew since 2007 use the new Military Flight Information Management System (MFIMS) which was rolled out to the squadrons of all three services to replace the older M-ALFINS system. MFIMS incorporates; NOTAM, flight planning with pre-booking and the allocation process. Pilots of civilian aircraft are required to use the Low-level Civil Aircraft Notification Procedure (CANP) and book their low-flying sorties with the LFBC at Wittering. Civilian low-flying typically includes; helicopters working with underslung loads (USL), crop-spraying, aerial surveys and pipeline inspections. This information is distributed to military aircraft operators to assist them with their flight planning. Military pilots tend to not know where they are flying till on the day, the weather being a major factor in their decision making. Generally tasks are allocated to pilots by someone higher up in seniority. On the day of the proposed sortie, the pilot or formation leader will spend up to three hours preparing for the flight. In this time it must be booked, planned, signed for and briefed so everyone involved is aware of what is going to happen, only then can they fly the mission. Analyse the threat

The tasks are varied according to the nature of the threat and the capabilities of the aircraft it could be an air-to-ground strike, reconnaissance or Close Air Support (CAS). The pilot or mission leader for multi-aircraft formations determines what needs to be done to execute the mission. The threats needs to be analysed, a strategy decided upon and appropriate weapons selected. If Laser Guided Weapons (LGB) are to be utilised then the aircraft will be flown at medium level over the target area with low-level as an option to and from the target. In the UK there are ranges such as Spadeadam in Cumbria which can simulate threats. An experienced Harrier weapons instructor described tasking as; “Initially aircrew are given a piece of paper with a description of the target, the mission leader will then decide what weapons to use against it. We have to ensure we have the right weapon, right conditions of impact etc”. Sorties are usually more than one aircraft, two, four or even eight ship formations so strikes need to be coordinated by timing and direction to target with simultaneous strikes from different directions. Apart from simulated ground to air threats in the training environment aircrew may need to be vigilant for an air to air threat. A NATO procedure known as 'Fighting Edge' is available to NATO frontline fighters. This set of rules to enable pilots to operate safely and requires participating aircraft to use transmit a code from the transponder to say that their fighter can be 'bounced' during the mission. An F-15E Strike Eagle pilot revealed; "It is dependant on those who want to participate, some days there are no jets, other days there can be a few, RAF jets use the system regularly." Mission Planning To plan a low-level training sortie, safety is a major consideration, a weather ‘Met’ briefing is studied for the locations selected, concentrations of birds, NOTAMS and Royal Flights all need to be taken in to account. A pilot may need to telephone to find out more about a particular NOTAM. Flying to a low-level training area is not so straight forward; flying over cities, towns and airports have to be avoided as well as the ever increasing civilian airways. Air bases on the eastern side of England if they are to fly in Wales (LFA 7) plan a route using special air corridors to enable them to cross the civilian airways. The Lichfield Corridor is set at 14,000 feet once through it they can descend to low-level in the Clee Hills for example.

A particular aircraft type may have its own bespoke mission planning software which can be used outside the aircraft and transferred to it for the mission. Tornado aircrew will use the Tornado Advanced Mission Planning Aid (TAMPA) to plan an entire sortie.

Mission planning is no easy task there are many aspects to it, often there are tight time constraints. A Qualified Weapons Instructor described the process; “Timings to the second ‘time on target’ and way points on the route need to be set. You have to decide what weapons are to be put on the jet and fill out a form for the engineers. There is also documentation for the jet, radio frequencies, weapons loaded and for the fuel set-up. The flight brief takes 30 minutes, how we are going to hit the target, the coordination with the other jets, how are we going to get back to the airfield? To do all this in less than three hours means you have to work pretty hard”. All mission planning information is transferred to the aircraft where it can be similarly displayed in the cockpit. A printed copy of the maps and other mission information is also taken to the aircraft as a backup should the electronic systems fail. Each mission is planned to match training needs and to facilitate as many tasks as is possible during the sortie. “We don’t just take-off from Marham and fly out at low-level; we go low-level where it best suits our training. We leave at medium level not just transiting we will be practising medium level scenarios en route before we drop in to low-level”, explained Sqn Ldr Beardmore, adding; “The areas we fly at low-level are picked to fit in with the training requirement. We go where the training benefits all. We may be working with air support guys on the ground that are learning how to Forward Air Control (FAC), or working with our image analysts who might need to analyse a particular activity”.

Post flight briefing Following completion of the sortie, crews are debriefed by the tasking officer, to make sure as much value as possible has been gained. Aircrew fill out more paperwork with the actual timings flown within the LFA, the actual route flown as it may be different to the planned route due to avoiding poor weather, flocks of birds or attacks by other aircraft. All the head up footage is saved on a hard drive. All the low-level information gained from the sortie is retained for possible use should a complaint be raised on the MOD low-flying advisory service by a civilian who has been disturbed for any reason by a low-flying aircraft. Sqn Ldr Beardmore is responsible for monitoring and maintaining standards said; “We debrief thoroughly after each sortie to look at rules that may have been compromised, using cockpit video recordings, no one can go out thinking they can break the rules”. Every effort is made To make the UKLFS as safe as possible Sqn Ldr Hale, Officer Commanding LF Ops said; “Every effort is made to keep the low-fly system safe and to disturb the general public a little as possible. Our aim is for aircraft operating at low-level to be co-ordinated, de-conflicted and separated day and night. To reduce noise pollution we set minimum altitudes and maximum speeds (480 knots, 889 km/h) and the use of the aircraft’s afterburners (or reheat) are restricted”. The Politian’s decide where our military forces should be sent in times of conflict. It is important and reasonable that our aircrew are properly trained for the life-threatening environments they are sent to. A weapons instructor who has served in Iraq and Afghanistan said; “When we train and exercise with other nations we find we are the best at low-level flying. They are respectful of our low-flying abilities. It is a skill set we have developed over many years”. Low-level flying training is vital and should be as realistic as possible so that our pilots retain the lead in this important aspect of combat flying. |

|

| 'A show of force' - Tornado GR.4 (ZA452 '021') A 31 Squadron Tornado GR.4 with a 67-degree swept wing and afterburners on, practising a ‘show of force’ during a low-level training sortie. |

| “When we train and exercise with other nations we find we are the best at low-level flying”. |